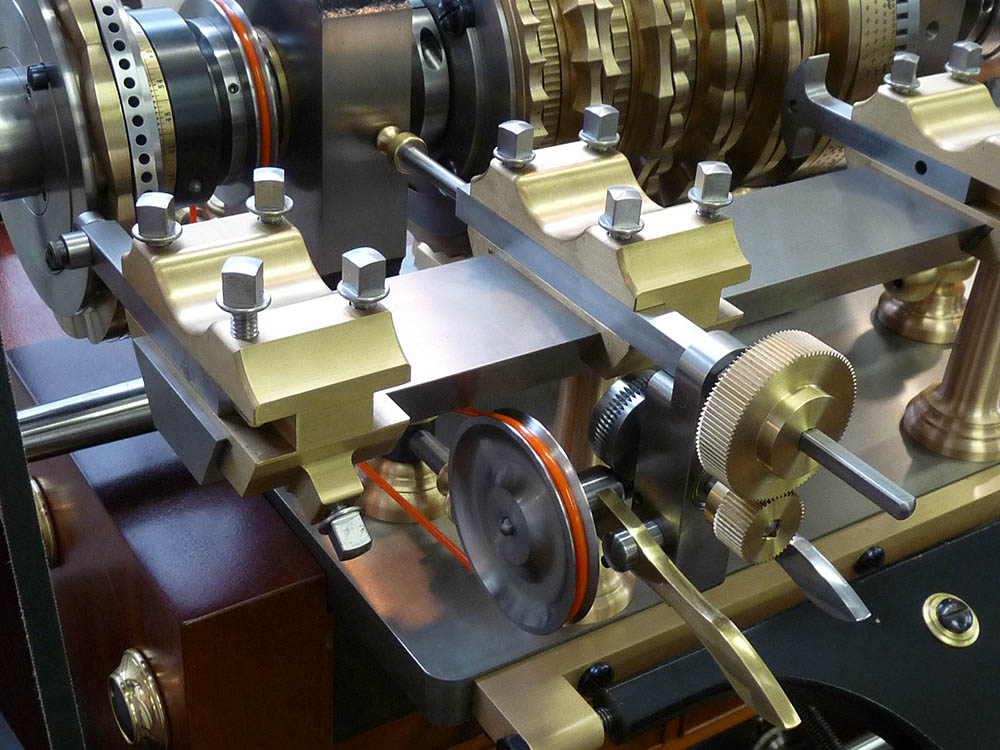

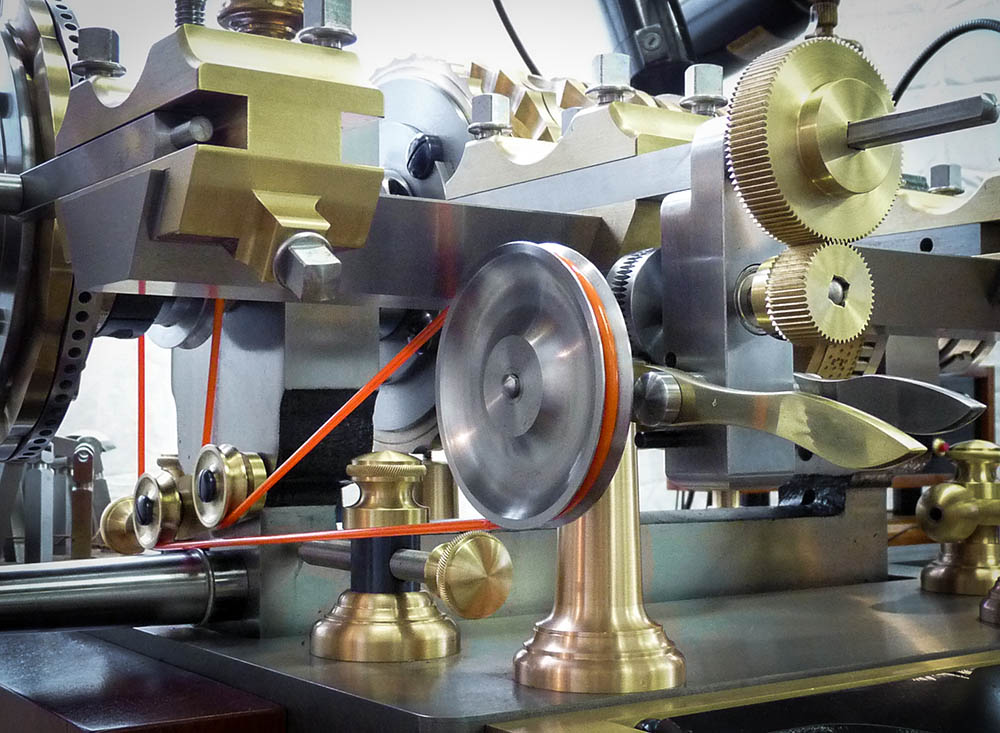

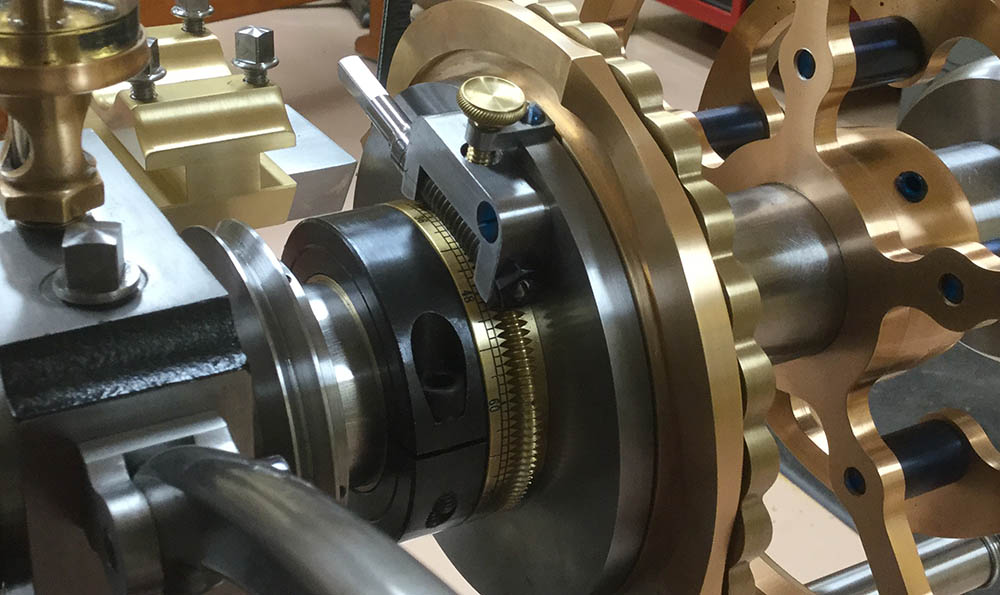

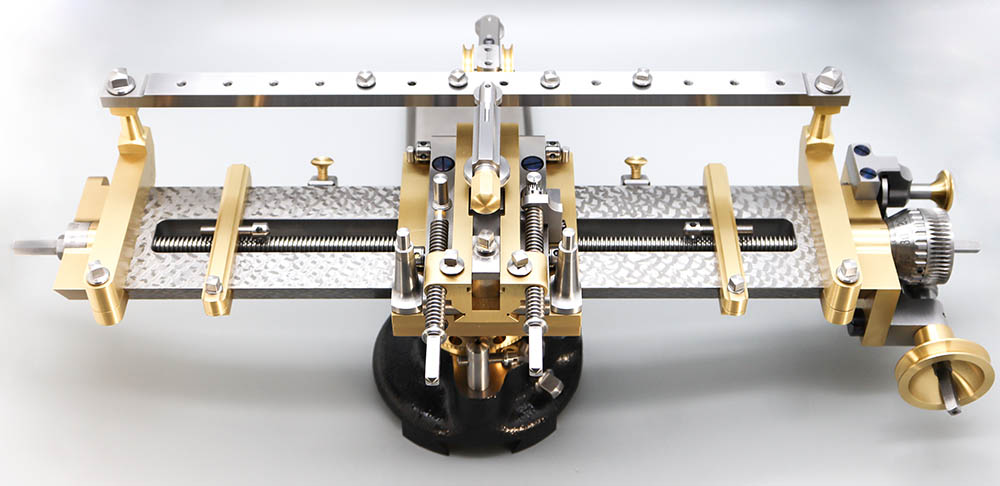

As with its early predecessors, the rosettes immediately draw you in. As they turn the light dances along their curved features in a brilliant display. The rosettes are contoured on their faces for “pumping,” where the spindle traverses left and right. A spacer is nestled between each pair of the 7” diameter rosettes. These smaller diameter spacers are more finely-contoured rosettes for doing guilloché work, a form of metal engraving. Fabergé’s famous eggs are well known examples of guilloché work.

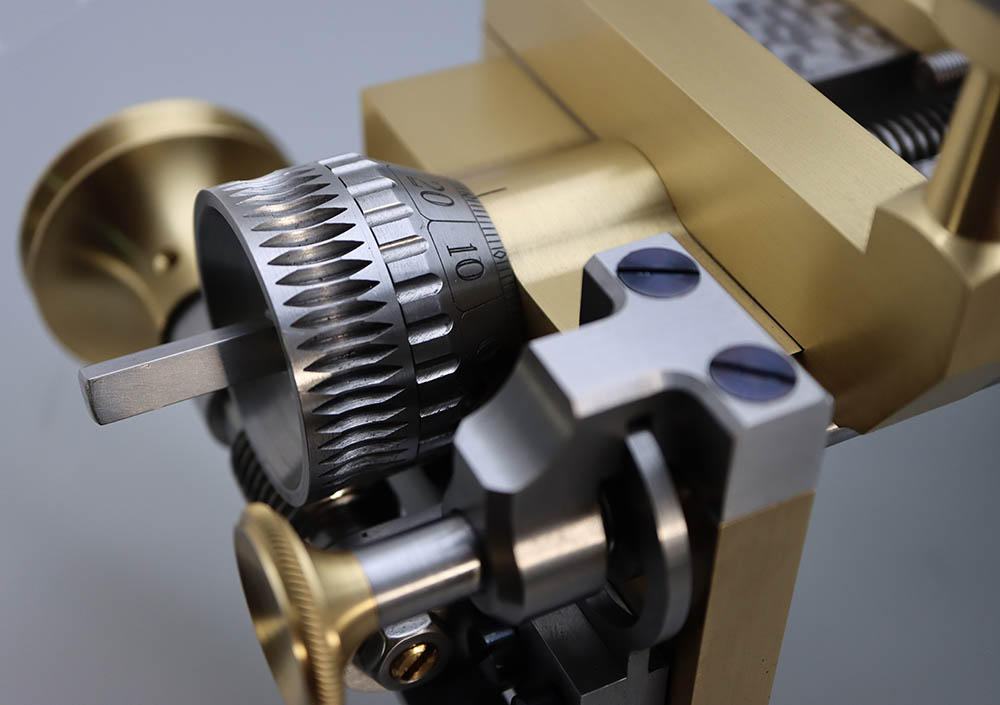

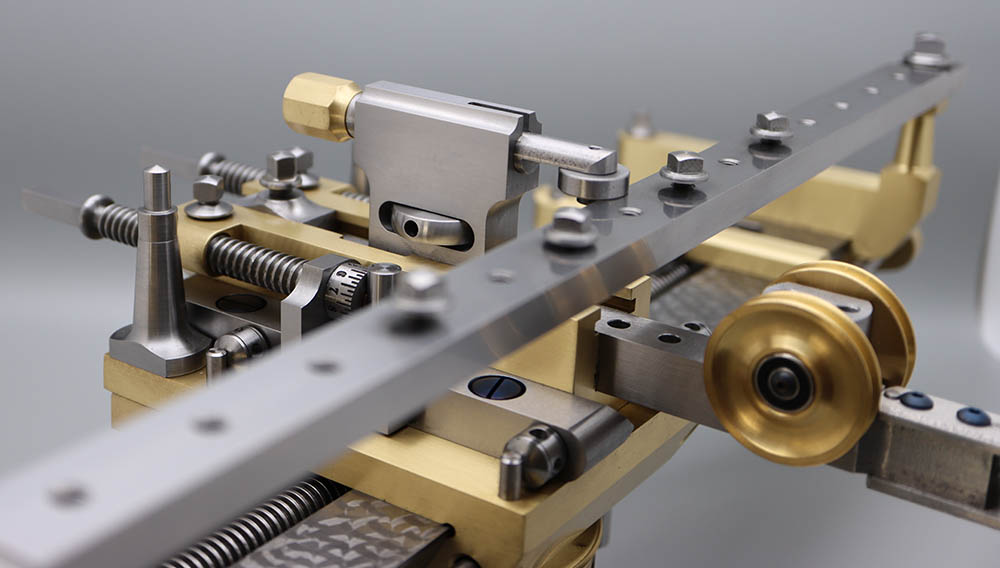

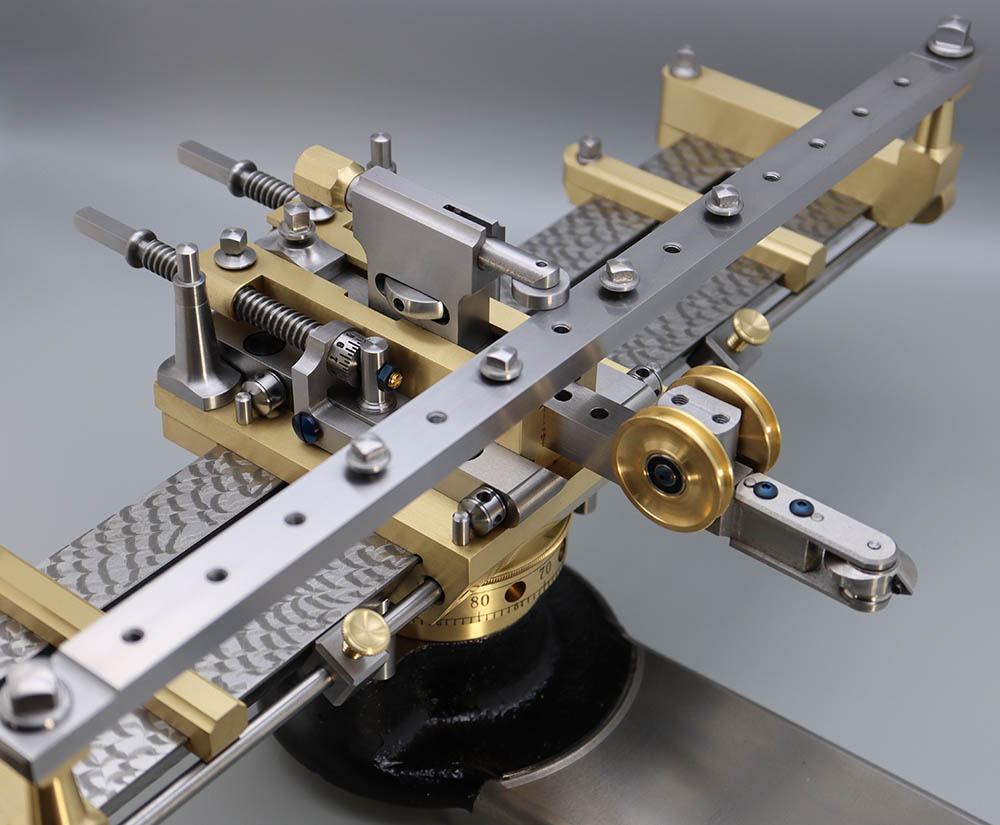

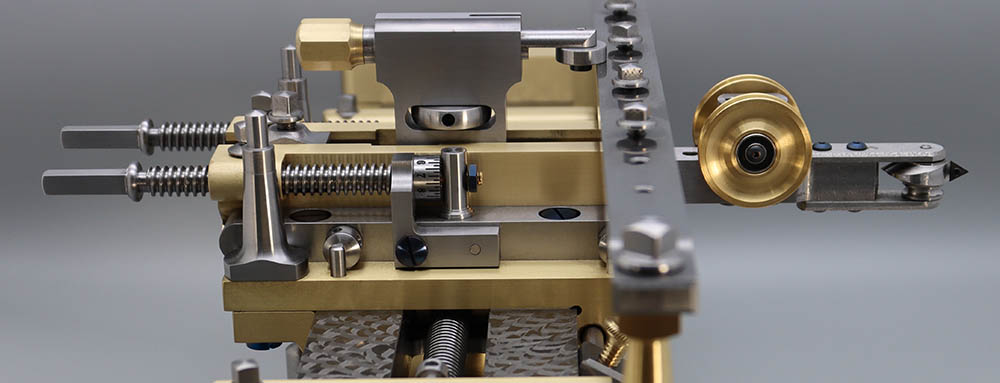

The slide rest is generally similar to those on earlier machines, but ball bearings have been mounted discreetly on the lead screw ends and the worm drive for smoother operation. Unlike most ornamental slide rests, the main graduated dial is adjustable, and, although not commonly done in the past, a second graduated dial is mounted on the opposite end of the lead screw, with drive squares on both ends of the screw. It also has a curvilinear slide with interchangeable touches that allow the touch to be matched to the diameters of various cutter heads.

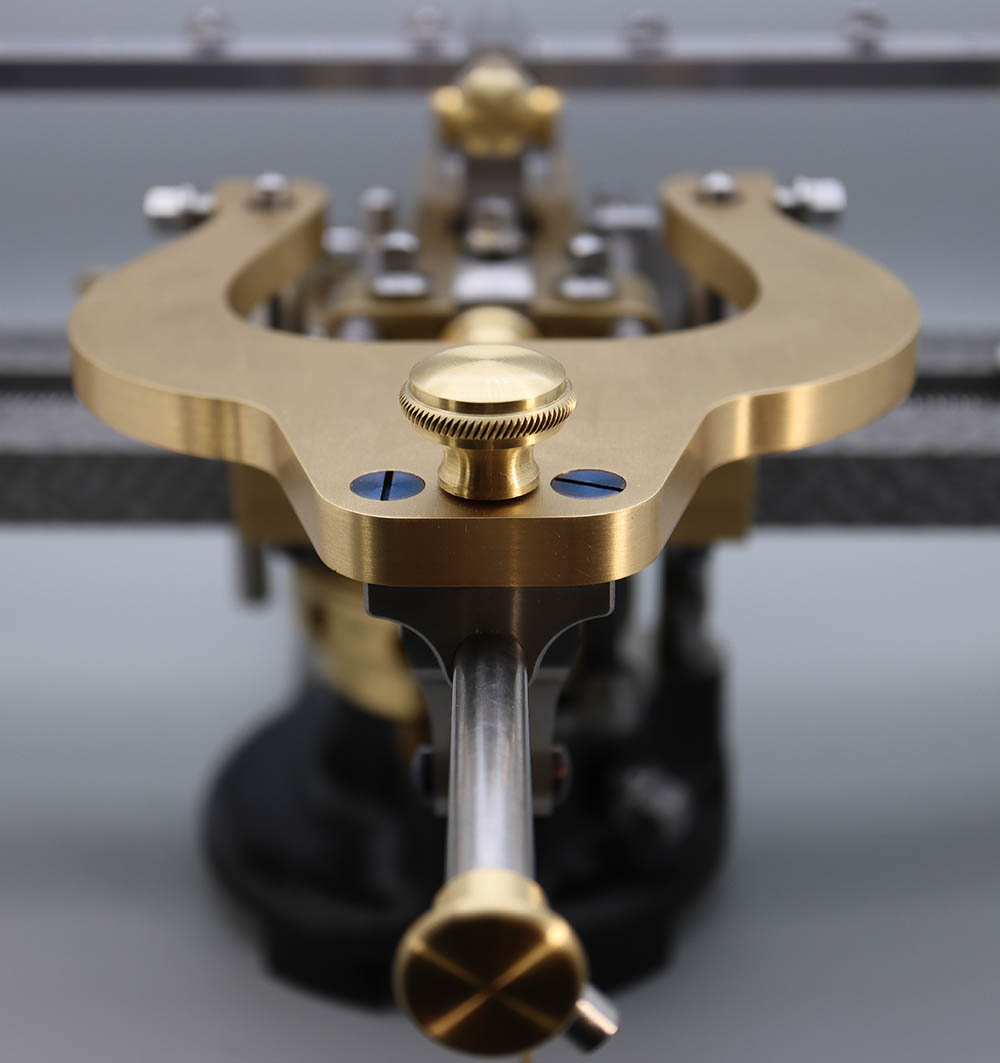

To accommodate “fixed tool” work, the MADE rose engine is supplied with a “headstock retractor”. Since, by definition, the cutter is fixed, the work piece must be gradually brought into the cutter rather than the more conventional situation where the cutter is fed into the work. A headstock retractor is essentially a moving stop, timed to the spindle, that allows a very gradual increase in the amplitude of the headstock’s rocking motion. As the retractor’s stop operates, the rosette is brought very slowly and continuously into increasing contact with the touch. The work piece, guided by the touch’s contact with the rosette, is fed gradually into the fixed cutting tool at a depth of cut that is frequently less than .001” per rotation of the work piece. The retractor has interchangeable gears so the depth of cut can be varied.

The traditional ornamental turning chucks are reproduced for the MADE lathe with a few changes. Most of these changes come as the makers stand on the shoulders of the Holtzapffels and others. One of the innovations is that the straight line chuck has a horizontal slide which allows the work to be moved rather than moving the cutter and slide rest, essential in getting a true form from the rosette of a traditional rose engine. Another innovation is the “double eccentric” chuck which allows eccentric adjustment in two directions. The MADE elliptical chuck is a traditional design, but made with more mass.

The origin of the MADE lathe can be traced to a meeting of Ornamental Tuners International in the fall of 2006 where Jeremy Soulsby, a noted English ornamental turner, delivered a lecture on his work in fixed tool turning. Mr. Soulsby had designed and built a lathe to do the type of work done in the 16th and 17th century when all rose engine work was done with the “fixed tool” technique. Fixed tool work is so called because the tools are ground to particular profiles and do not rotate as they do in the Holtzapffel type cutting frames. Both Al Collins and David Lindow were inspired by Mr. Soulsby’s presentation. Al spent the next few years developing techniques of his own to do fixed tool work on the lathe he had built. David was preoccupied at the time with developing a production lathe he’d introduced with a partner in 2006.

In 2010, Al and David entered into a joint project to develop a newly designed headstock retractor intended for use on the rose engine Al had made over a decade before. With the success of the headstock retractor behind them, Al called David and asked if he thought a heavier headstock could be made and fitted to Al’s lathe. David immediately suggested an entirely new lathe be built. As has often been said, when one is headed off a precipice one seldom goes alone. David soon called Mike Stacey of Columbus Machine Works and asked if he had interest in the project. Mike was in. Ever the patron of all things ornamental turning, Eric Spatt soon joined, and four MADE Lathe prototypes were under way. The first of the four prototypes came almost two years later and was introduced at the 2012 meeting of Ornamental Turners International in Scranton, PA. However, there were bugs to be worked out, and over the next two years improvements were made. David Lindow and Mike Stacey decided they would make a production run of 10 lathes, and in the fall of 2014, they showed the improved lathe at that year’s Ornamental Turners meetings and began to take orders. It would be another three years of work before delivery of the production models began.

The MADE lathe rounds out the Plumier Foundation’s collection of lathes. As parts for it are currently in production and readily available, it gives students the opportunity to learn on a machine with all the beauty and nuances of the antique machines, but without the stress-inducing risk of damaging something irreplaceable.