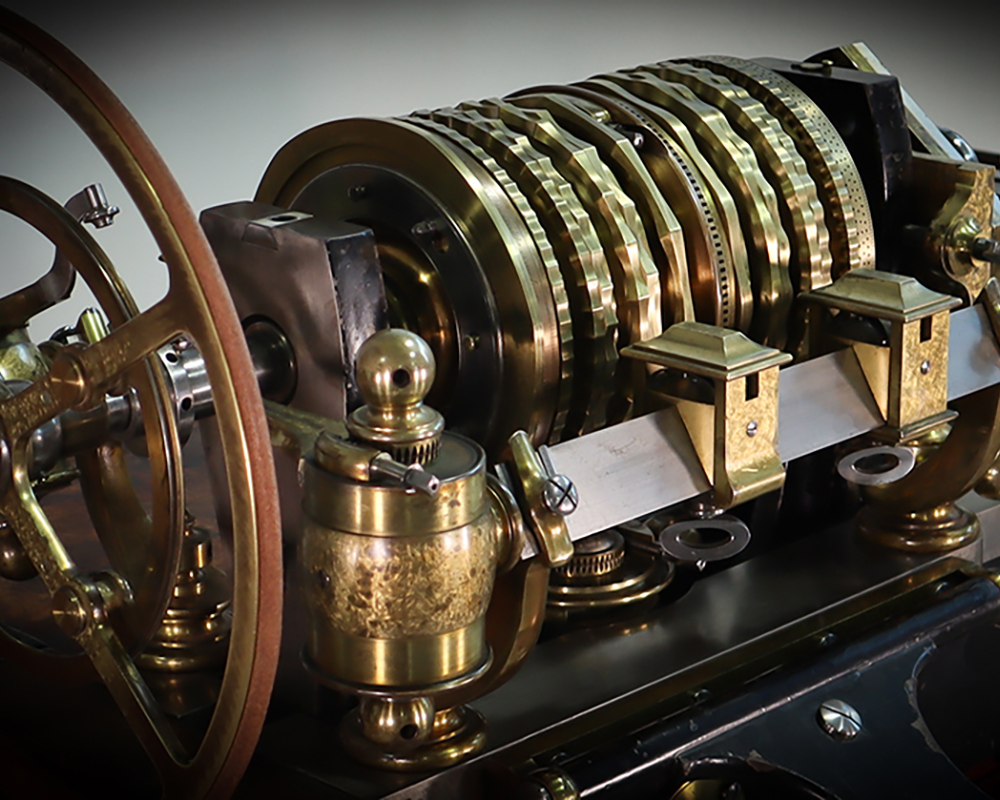

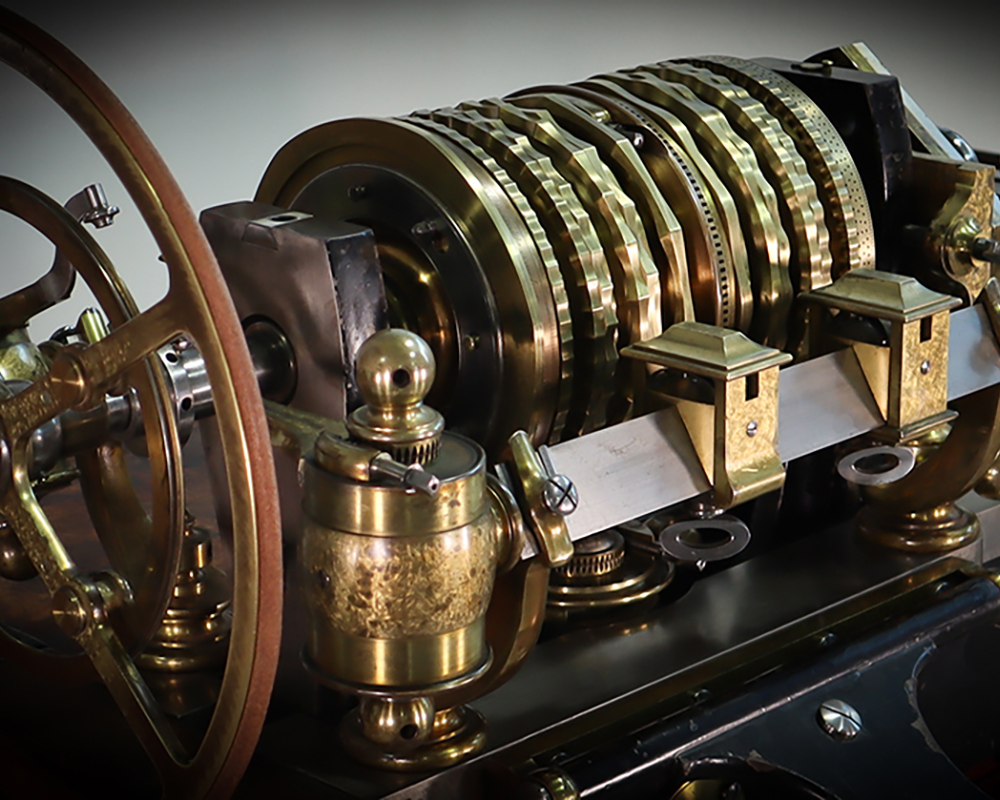

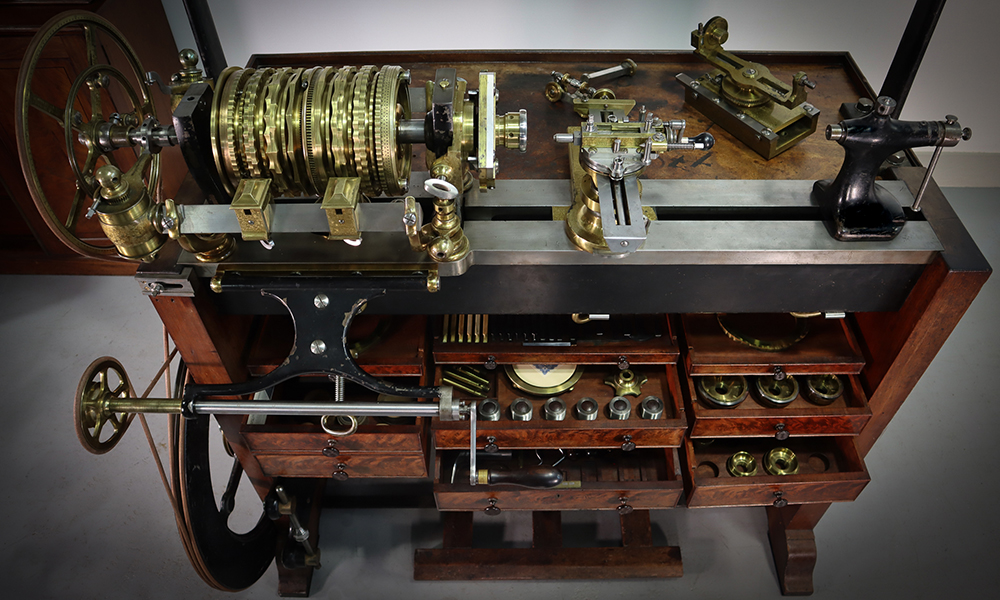

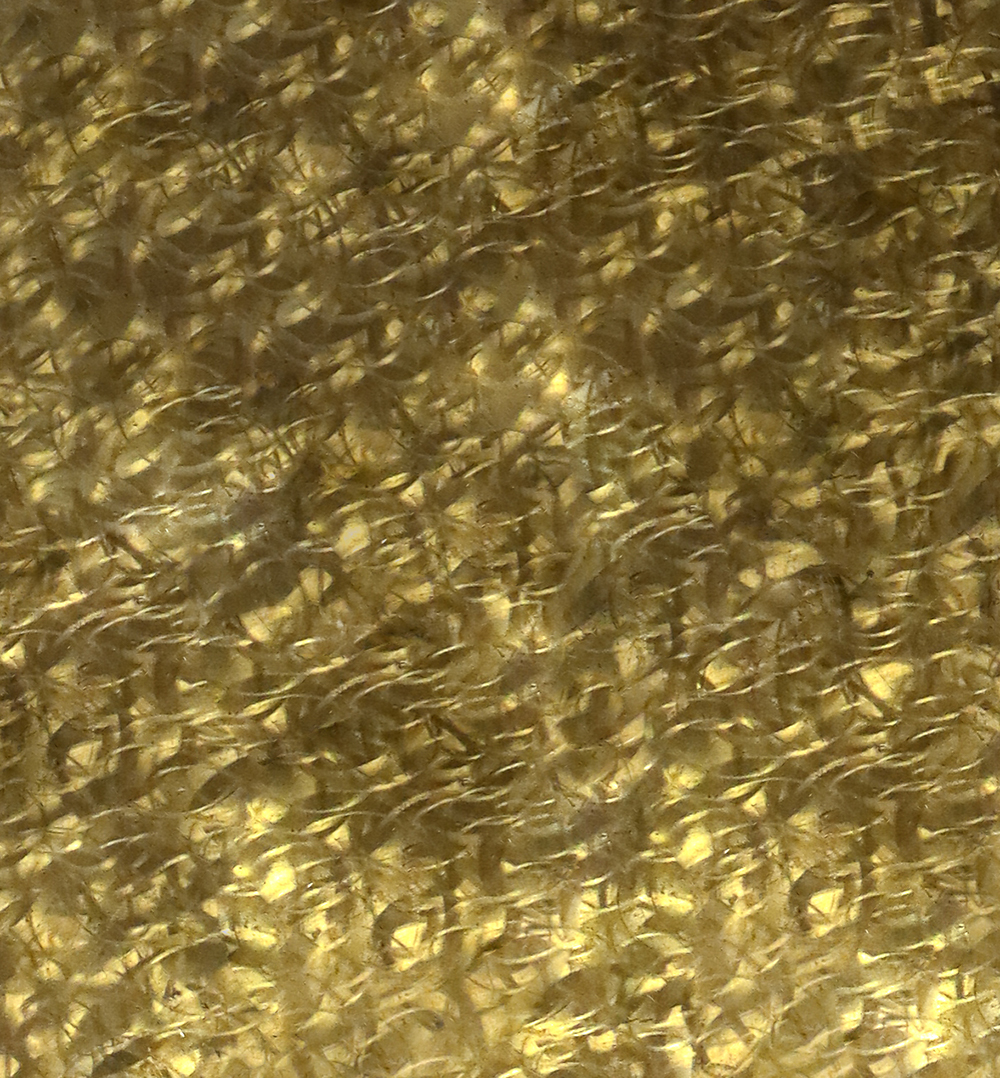

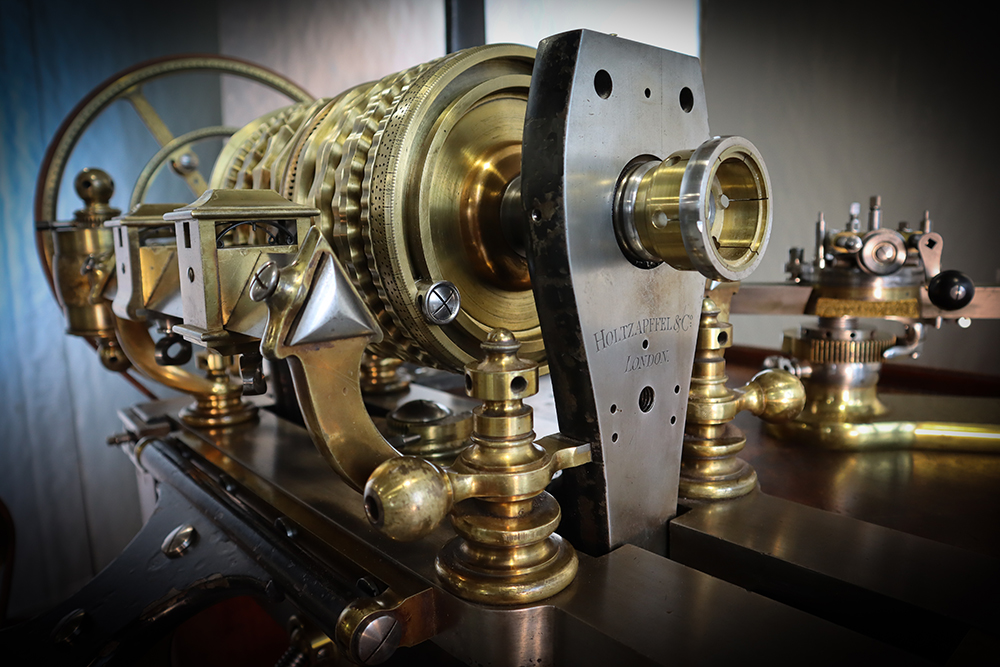

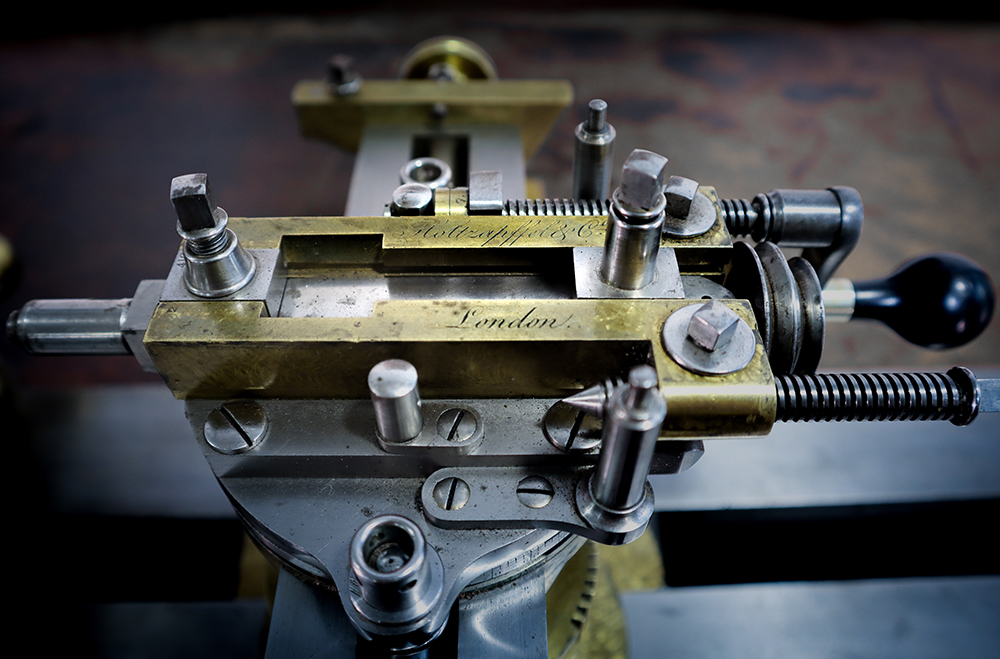

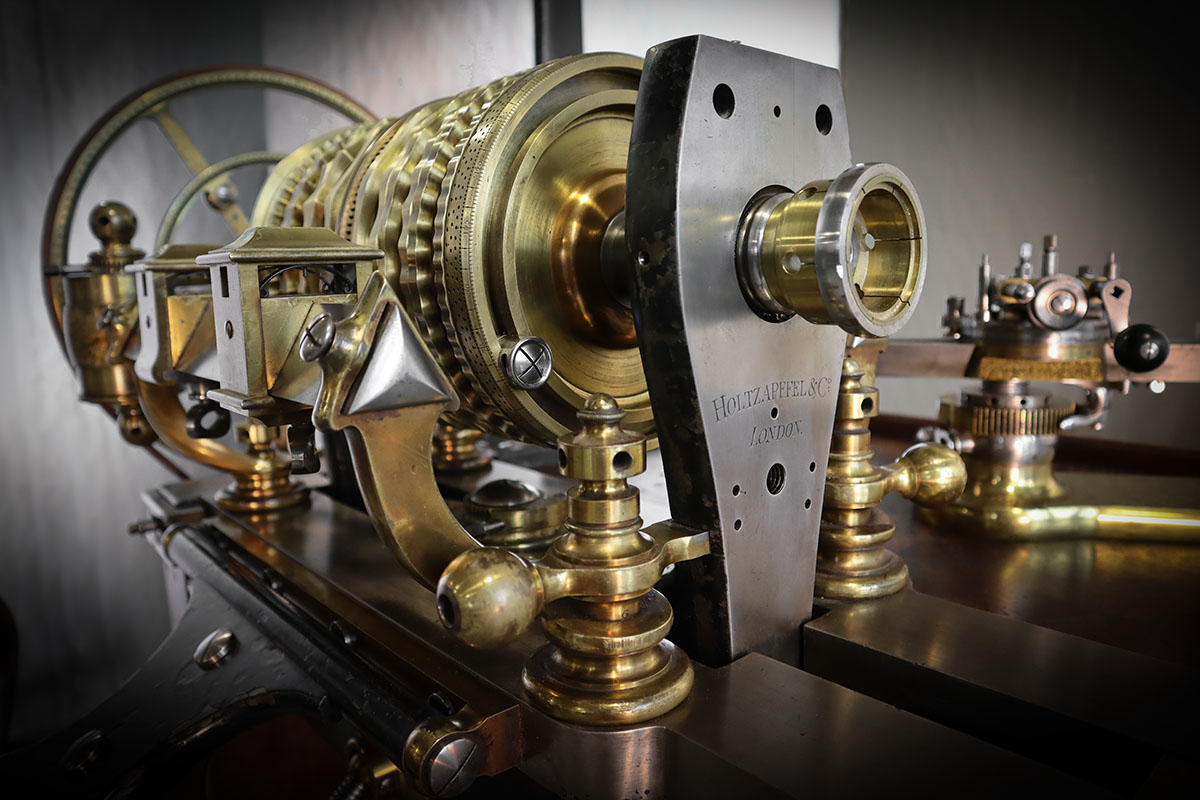

When one first sees this machine, the senses are overwhelmed to the degree that details don’t come into focus immediately. Its form is sculptural, and even those not from the mechanical world know they are in the presence of greatness. Many comment that it’s reminiscent of H.G. Wells’ immortal “Time Machine,” and so it is with its combination of mahogany, iron, and highly finished brass, all demonstrating the decorative zeal typical of the Victorian age. On first exposure, one is drawn close to the machine, but then one soon feels the need to step back to get an overall view. After a period of observation from a distance, the details begin to emerge. The eyes are always drawn first to the headstock with its ornate rosettes; but then other features come into focus. The pulleys are a work of art. The largest pulley is iron and serves as a flywheel as well. It still retains its original Japanning with the patina showing its nearly 200 years. The ornate brass pulley on the headstock appears delicate despite its being 14” in diameter. Next to tempt the eyes the eyes is the cabinet under the bed. The drawer fronts of matched, crotch-figured, Cuban mahogany pull one in. Ornamentally-turned drawer pulls of African Blackwood reflect light to form figure eight holograms. Opening a drawer reveals tools and accessories nested in fitted mahogany compartments.

One drawer contains the touches made of ivory and steel; one is adjustable for complex patterns. Two drawers contain beautifully-made split rosettes for the auxiliary holder and two other drawers hold one rosette each. The holding chucks fill two drawers. One drawer contains screw drivers with elegant fluting and those exceptionally thin blades so typical of Holtzapffel tools. The tympan chucks with their leather backing sit alongside the thread bobbins. In addition to the rosettes in these drawers there are two separate boxes that contain a total of 24 more rosettes. One’s whole sense is that a treasure chest has just been discovered.

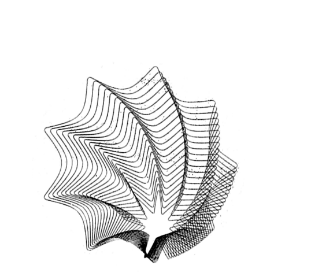

The rosettes, of course, draw the most attention as they are what define the machine and enable it to create a seemingly infinite number of forms.

However, on closer inspection, one soon notices the beauty of the smaller details, such as the hand-engraved fonts chosen for the numbers and letters on the index wheel and swash plate. There is much more to appreciate on the lathe, of course, but now the tall cabinet of accessories beckons.

On opening the cabinet doors, one is overwhelmed again. There is simply too much visual detail to absorb, forcing one to step back and refocus. Adopting a more methodical approach, one begins to inspect the cabinet’s contents piece by piece. First to strike the eye is the geometric chuck, a mechanical marvel made to Ibbetson’s design. Perhaps next to demand attention is the drive on the straight line chuck with its elegant chains. Reaction to the contents of the cabinet varies. Some see it as a shrine and are reluctant to disturb the cabinet’s treasures. But these tools were meant to be handled, made to be used. One by one the pieces are picked up and admired. Each tool still glistens after almost two centuries, and the light dances from every facet of their jewel-like surfaces. In addition to the geometric and straight line chucks, there are the regular holding chucks along with the two elliptical chucks, a spherical chuck, a column fluting chuck (pen chuck), eccentric chuck, numerous cutting frames, various pieces and parts that belong to each of these tools, and the original ornamental slide rest.

The bottom doors of the cabinet open to reveal the bank of drawers containing more of the cabinet’s ornamental turning wealth. Amidst the original tooling are pieces and parts, drives and gears, and other apparatus made by the lathe’s various owners through the years, especially Warren Ogden, Jr.

The overall effect of the above inspection is to make clear why so many consider this the best rose engine in the world.

John Taylor, Esq. was the original purchaser of the lathe. He was a civil engineer, but to simply identify him by that designation would be an understatement. He started in the chemical business but eventually went into mining. Taylor had exception skills in financing and managing mining operations; he was known for taking mines that were not productive and reorganizing them to make them profitable once again. After the Mexican Revolution of the 1820’s, he headed two mining operations in Mexico. They were the sole failure on his record, and the losses incurred would have bankrupted even most wealthy entrepreneurs of his day; however, the enormous losses appear to have affected him little. Taylor also owned Holtzapffel No. 1902 which he bought new in 1847. He kept No. 1636 until his death in 1863. It was then sold to an unnamed engineer, a regular customer of Holtzapffel & Co., whom they described as “an old and careful turner.” There is conjecture about who this buyer might have been, but nothing with firm documentation.

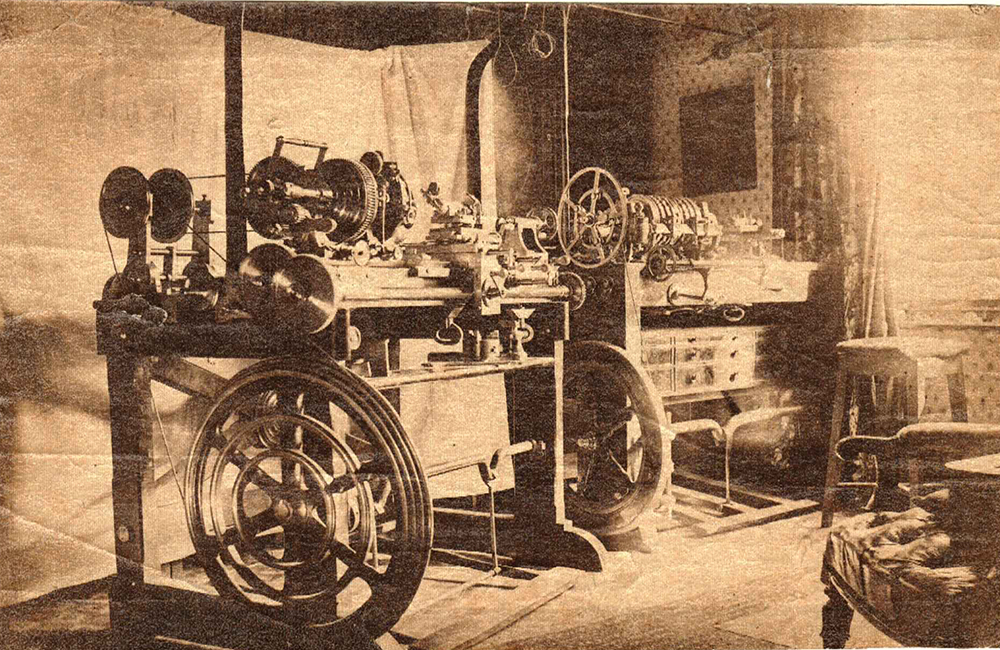

In 1869 the lathe once again entered the hands of the Holtzapffel firm and was sold to William John Potts Chatto. Chatto was said to have had no “occupation other than that of a 19th century gentleman of private means.” Nevertheless, he was “respected by all classes” mostly because of his genial disposition. Upon his death, the disposal of his workshop was left in the hands of J.H. Evans who also built ornamental turning lathes and wrote extensively on the subject. Interestingly, there is a picture from about 1873 of the lathes in Mr. Chatto’s living room, showing Holtzapffel No.1636 sitting next to a Goyen ornamental turning lathe.

Chatto died in 1882 after which Rev. Willoughby John Edward Rooke acquired the lathe. Rooke was a Vicar and died in 1902 at age 91. James Edward Galliford then bough the lathe and kept it till his death in 1933. Galliford was a silver medalist of the Turning Company.

Walter Gordon Hindes bought the lathe from Galliford’s widow after having traveled to see it several times. He was 18 years old and a Midland Bank employee. Holtzapffel No.1636 would be his fourth ornamental lathe even at that young age. Hindes would keep the lathe for 21 years, then sell it to Warren Greene Ogden, Jr. Hindes used the proceeds from the sale to finance three years of engineering school for his son.

Warren Greene Ogden, Jr. was a toolmaker and the superintendent of the experimental machine shop at Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he developed tooling for machining nuclear materials for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. He lived in Lincoln, MA; and it was through his purchase that the lathe found its way to America. Richard Miller acquired it from Warren Ogden.

In December, 2012, Bill Ruprecht bought Holtzapffel #1636 to the be the centerpiece of the working collection at the Plumier Foundation.