“I have loaded into our facility perhaps 25 crates which house among other things- five 19th c lathes and significant cabinets and cutting frames …… it’s all there but not pretty. Can’t wait for you to dive into assembly and engage with this stuff.” So went an email from Bill Ruprecht to David Lindow on December 3, 2019. David’s response was simply, “Thanks. See you in the morning.” It was a pretty inauspicious exchange given what was about to happen.

Bill had caught the ornamental turning bug in the 1970’s and had been buying and storing machines since the mid 1980’s. He had purchased five 19th century ornamental turning lathes, two of which were rose engines and all had been placed in climate controlled art storage. Some of these lathes Bill had never seen in person, and the most recent one he had purchased had been crated for storage some 5 plus years earlier. It wasn’t just a stack of crates that were about to opened. The physical manifestation of a decades long dream was about to appear. Shop space had been obtained, and the crated machines delivered. Those machines were just waiting, for the right moment and the right people to release them from their confines and restore their glory.

The Plumier’s Foundation’s new shop is located in Port Chester, NY. Its 3,500 square foot shop space is located in an impeccably clean, modern building. A train station within easy walking distance gives quick and ready access to NYC, yet the countryside is just a few minutes away. Also within walking distance, local restaurants abound, offering a wide variety of dining opportunities. The shop is bright and cheerful with two large windows that fill the shop with natural light. It’s a seemingly perfect setting for the Plumier Foundation to reintroduce old techniques for making beautiful objects, and, in the process, foster conversation and thought, build relationships and open minds to new possibilities.

David didn’t have to look far to find volunteers to help unpack the crates. In addition to his son, Christian, he recruited Frank Dorion, Anthony Nappi, and Josh Huether to uncrate and set up these old lathes. Each person listed had a specific skill set that contributed to the process, and each has experience in handling, assembling, and restoring old machine tools. Each entered the room and marveled in turn at the 25 crates waiting to be unpacked. Figures 1, 2, and 3, show the room in its vastness as we began opening the crates.

Frank and Christian teamed up and chose to start unpacking the Bower lathe. Josh and David took on Holtzapffel lathe No. 2410. Anthony would come in later and help wherever he was needed at the moment. Of course, at the outset, there was a good deal of confusion over which crates went with which lathe. Soon it became apparent that each lathe had been packed by a different company so the crates could be divided up on that basis. Their contents, however, were still a mystery. There were 7 large crates from one company, and Josh, assuming these crates contained multiple lathes, wondered how we’d know what stuff went with what lathe. David looked at him, a bit amused, and said, “This is all one lathe!” Astonishingly, it was.

The two respective crews began to open the crates with the objective of finding the bases for the lathes, the beds, and the other main structural parts necessary to start setting them up. Of course, the bed and base are usually the heaviest part of a machine. and Murphy’s Law prevailed. The stuff needed first was on the bottom of the crate and all the smaller parts had to be extricated and set aside before assembly could begin.

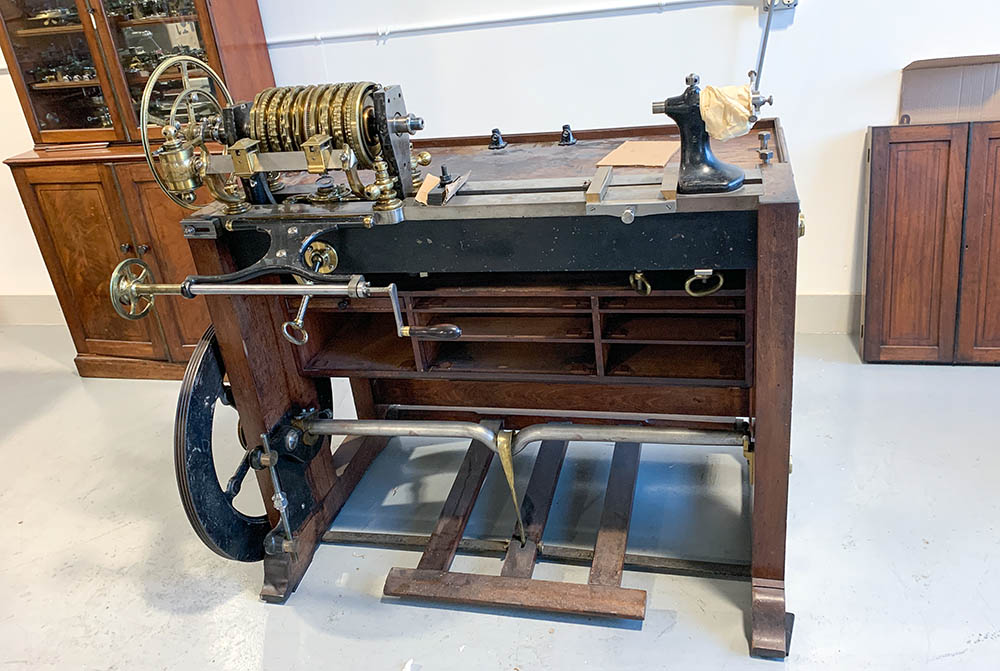

The John Bower lathe went together the first day, and its tooling was sorted out that first day as well. Even before it was completely together, it had earned the admiration of all in the shop. The lathe was just perfection in every detail, from the elegant lines of its frame down to the fitted drawer containing the horn handled screw drivers with their exquisite lines and curves. (Learn more about the Bower Lathe “Here” –link to Bower page)

While the other crews worked on unpacking the ornamental turning lathes, Bill Ruprecht and his friend Gabby assembled the workbench The Plumier Foundation bought from Mark Hicks (Plate 11).

Mark builds extremely heavy-duty joiner’s benches in the traditional way, using hardware from Bench Crafted, a U.S. manufacturer of well thought out and extremely heavy-duty bench hardware. (Figure 8: Completed Plate 9 bench.)

Once the lathes were assembled and the tooling cabinets put in place, the process of unpacking the tooling began. Almost every tool had been individually wrapped by the packers, so the unpacking process had sort of a Christmas morning feel to it.

As each tool was unwrapped, it was placed on tables there for the purpose. Soon the crew was gazing at an amazing array of the finest work Victorian technology could produce. The effect was stunning! Josh, who does magnificent finish and assembly work on the MADE Lathes as well as handing some production, could not hold back his excitement over the impeccable quality and finish of the Holtzapffel tooling. He held up parts repeatedly to point out the examples of exquisite workmanship he was holding. He was not alone in doing this, as others soon found masterpieces to show as well.

Crate by crate, box by box, each piece of tooling was unpacked and placed where it belonged. Astonishingly, there was virtually no rust on anything from storage. One lathe, packed in the mid 1980’s, had just a tiny bit of corrosion, but, fortunately, the problem cleaned up well.

Chisels, so many chisels! With two triptych cabinets and three double-door cabinets that housed 50-75 wooden handled chisels each, finding the right home for the hundreds of chisels on the tables presented a sizeable task.

Anthony went at the task head on. He sorted the chisels, set by set, and placed them in the cabinet where they belonged.

Anthony sorting chisels.

Filled Triptych.

Piece by piece and part by part the remainder of the tooling was placed in the cabinets and drawers from which it had so long been absent

Base drawer for Holtzapffel No. 1636 with tooling nested

Tooling Cabinet for Holtzapffel No. 1636 with tools nested.)

In the midst of it all there was a head scratching moment. Holtzapffel No. 1636, the massive rose engine, was on a rolling base about a foot high. It needed to be lifted of this rolling base and set into position on the shop floor.

Many options were discussed, from using the brute strength of several men to using a chain hoist hung from the rafters, but the wisdom of Frank Dorion prevailed. We’d reinforce a scaffold left by the electrical crew and use a chain hoist to gently lift it off of the cart and set it down. And yes, all breathed a sigh of relief when that exercise was accomplished successfully.

All of the period ornamental lathes were now in place.

With the machines and tooling unpacked, sorted and positioned in their permanent locations, the crew stepped back and surveyed their handiwork. Bill, always a man of few words, had his thoughts betrayed by his demeanor. Having started toward this goal decades before, this day had been a watershed moment for him. Some of these machines he’d never laid eyes on; others he’d not seen in years. The ornamental turning section of The Plumier Foundation’s shop was in place and almost ready to run. The process took five days spread over a couple of weeks, but there was so much more to do.