Seldom is anything made without drawing inspiration from things that came before. While this contribution from the past may be easy to discern, we don’t notice it most of the time because the inspiration often comes from a much different context, so the parallel ideas are not always obvious. The converse of this is true as well; we view things from the past without being alert for ideas parallel to our current efforts and miss new opportunities as a result.

In this vein, we thought it would be a good idea to show some of our work, and show the inspiration behind it as well. Often, our resulting product wouldn’t be seen as having been derived from the original source because the original idea has evolved through a process. Inspiration begets experimentation, and experimentation has a way of taking us to places we never would have thought of otherwise. Sometimes we like the results, sometimes not. Often, however, even those things that didn’t turn out quite like we hoped foster new ideas that do. We’re going to try to demonstrate that here. In

Below is a box that we recently made. We’ll track where the ideas came from and how we ended up here.

We will start with the top.

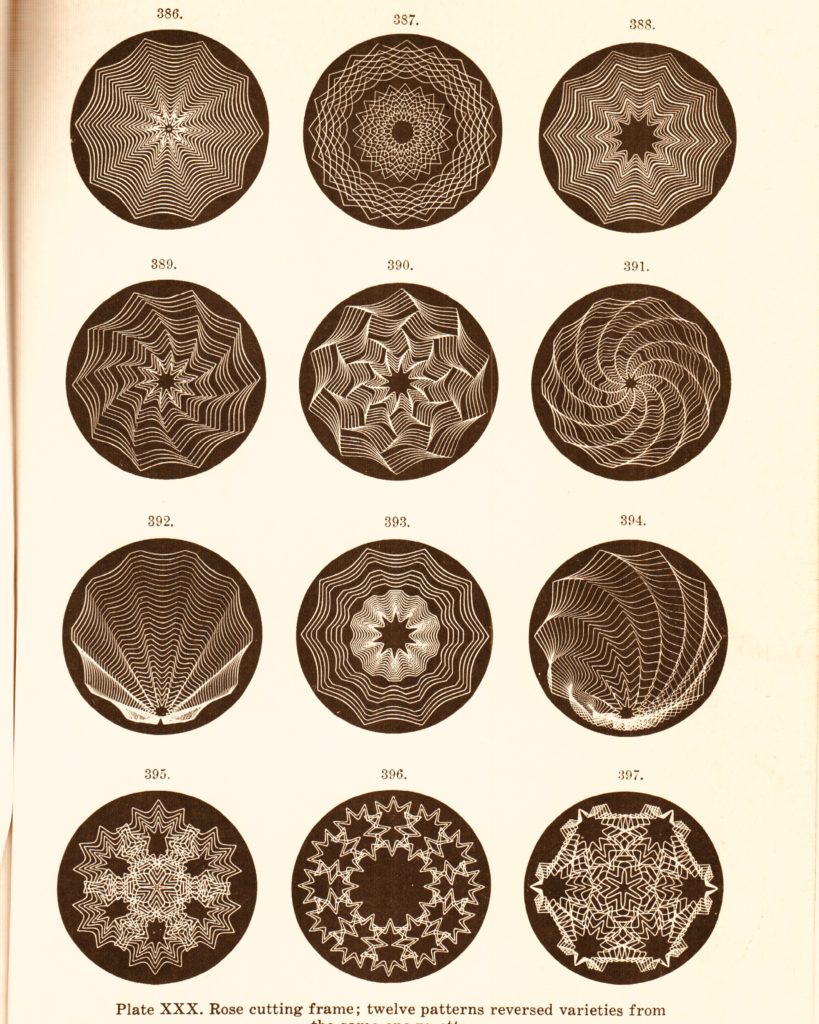

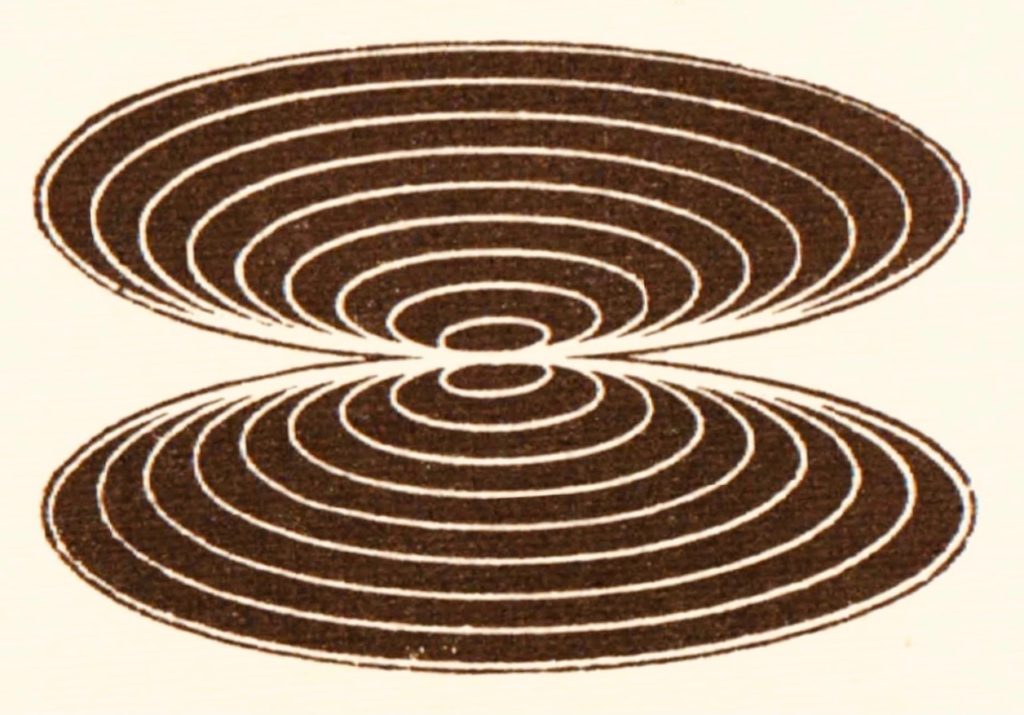

The double shell pattern on the lid evolved from a page in Holtzapffel Volume V. In the Holtzapffel version, the original pattern was produced on an ornamental lathe using a “rose cutting frame.” That particular cutting frame was not designed for use with a rotating cutter, so the patterns were produced by shallow cuts from a small fixed tool set into the tool box of the cutting frame. The resulting cuts were more or less two dimensional. However, because we were going to be using a rose engine, we could use a live tool, and that turned out to be a game changer for this pattern.

For our first foray into making the shell pattern, we used a horizontal cutting frame. Christian figured a real shell is three-dimensional so he decided to try adding that third dimension to the original Holtzapffel pattern. The result can be seen below.

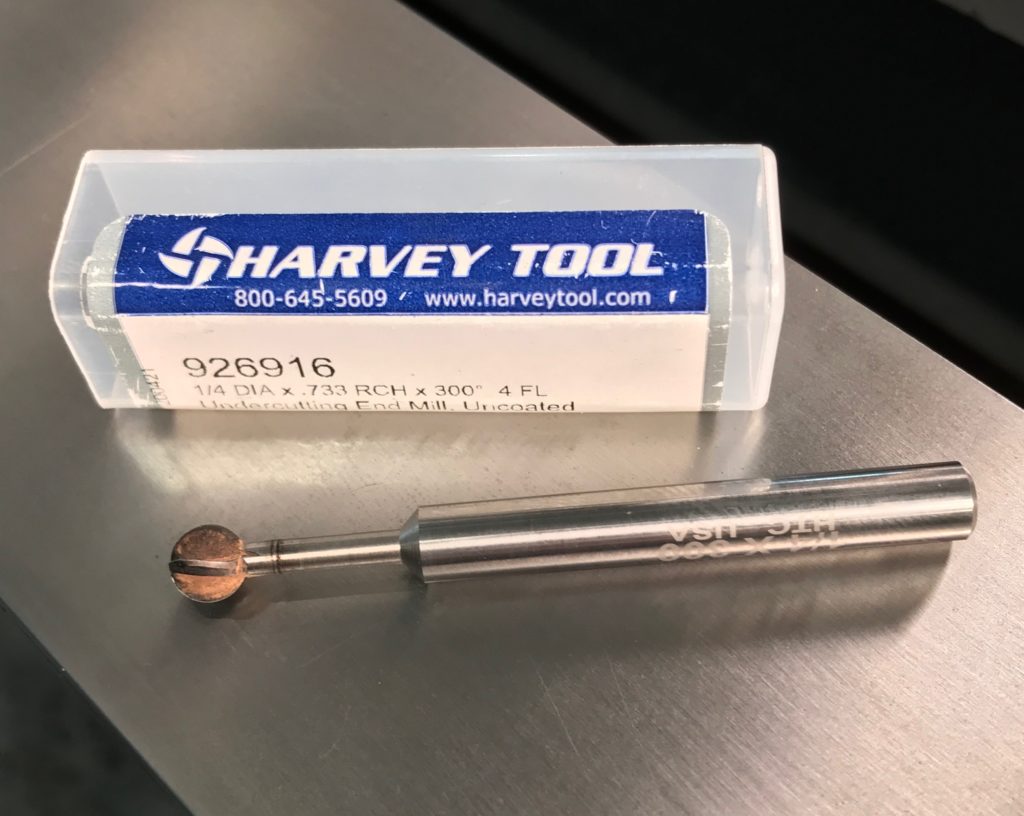

Generally, the result looked good. However, because the large diameter of the cutter head required a correspondingly large border, the size of the central pattern was restricted to be smaller than we preferred. A smaller diameter cutter was needed. We have a ball drill from Ornamental Cutters so Christian decided to give that a try.

As good as the first pattern was, it’s immediately obvious that the lid pattern (above) cut with the smaller diameter ball drill is an improvement. The central pattern is larger and the now smaller border is more pronounced and sculpted.

This pattern is accomplished with an eccentric chuck. The outer border is cut concentric to the spindle. Each successive cut requires that the slide rest be moved inward and the eccentric chuck be adjusted to almost the same amount.

But then there’s that other shell pattern on the same page of Holtzapffel V that has a twist, and it didn’t take long to start the trek down that road. The box lid below shows the results.

Every project is a preparation for the projects to come. This was no exception. These exercises with round boxes were studies in proportion, transitions, and techniques that we intended to apply to the elliptical boxes we planned to make.

Somewhere along the line, we realized that ball cutters could be purchased that had about 300 degrees of cutting surface. This meant an undercut was possible (see the African Blackwood box above). Whether one prefers that undercut or not is another question, but that question is impossible to answer without seeing samples.

Of course, the question “Why stop here?” quickly occurred to us. And once again, Holtzapffel Volume V provided the inspiration we needed.

Since we are standing on the Holtzapffels’ shoulders as our vantage point, there’s an irresistible temptation to “one up” them. That may be a tall order, but as long as one is indulging in hubris, why not go all out. Christian soon came up with the box lid below which required that both a rectilinear and an eccentric chuck be attached on top of the elliptical chuck. The undercut from the 300-degree ball cutter is more obvious on this lid pattern.

And so one’s work evolves. It’s influenced by pictures and drawings of related work, comments from others, and, most of all, burnished by experience. Repetition is also necessary for improvement, even if it doesn’t come naturally to us. There’s no substitute for it.

We’ll explore the patterns on the sides and bottoms of the above boxes in Part 2. Their evolution is no less interesting and no less the result of repetition as well.